Alan Baum

Alyssa Farm Planting/Harvesting

Land Clearing

When Morrell Agro Industries first leased land in Beltu from the Ethiopian government, it was covered in brush and trees. The land had to be cleared before planting could begin on the property, and a seed farm could be established. MAI employees had hoped that dozers would arrive at the property to help in the clearing, but they were slow to come. Only three dozers arrived, and two broke down within their first two days on the farm. There was a lot of frustration trying to decide what to do, in order to get the land cleared in time for planting.

Wes Haws was the farm manager at the time. He decided to make use of the abundance of idle manpower in the area and buy hand tools to begin clearing the land by hand. MAI began working with InfoMind, a company that deals with the hiring and management of employees. They hired local Ethiopian people to start chopping down the bushes and trees that cluttered the landscape.

When Alan Baum first flew out to the Alyssa farm, clearing work was underway. Flying over the property, Alan’s first impression caused him wonder why MAI was farming in that particular area of Ethiopia. On the way to the farm, he had seen lush, green plateaus and land suitable for farming. But, in Beltu, everything was brown. It was hot – well into the 90s. The soil profile was dry, and the only bushes, trees, and grasses growing were small and brown, surviving by pushing up through hard ground. It would be a miracle if farm crops grew successfully there.

In the meantime, Wes and the farm workers were trying to get the piles of brush and trees to burn on the property. This proved to be another challenge, as the thorny, loose piles were still too green to burn properly. This problem was solved by using loaders to push together the brush and tree debris and compact them into tighter piles.

Once the piles were packed together, they burned quite well. The lit fires at night were quite a spectacular sight, drawing the crews out to watch.

Slowly more dozers began to arrive at the farm. When five dozers were working the land together, a lot of ground was able to be cleared out and prepared for planting.

Preparing for Planting

Once the land was cleared, it had to be prepared for planting. Equipment was brought in to the farm to help accomplish this. Morrell Agro Industries purchased some of the needed equipment, while renting others.

Disc plows are a commonly implemented farm tool in Ethiopia. Disc plows are pulled behind tractors, penetrating the ground to plow it. Once the land at the Alyssa farm was cleared and burned, these disc plows were used to help turn over the soil. It was slow going, as the plows only took one meter of ground at a time. MAI had to use several plows at once to speed up the process.

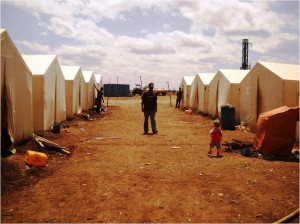

It was also a challenge to get all of the hired workers lined up and where they were supposed to be. The workers needed to be separated into different groups, so that they could work their own area of ground. All of these workers also needed a place to live while working on the property. So, MAI purchased tents, to use as temporary housing, for the hired employees, tractor drivers and MAI staff on the Alyssa farm.

Thorns, branches, and stumps, despite the crews’ best clearing efforts, still littered the ground while plowing was taking place. This caused a great many tire problems. The thorns were actually long enough, and hard enough, to penetrate tractor tires and flatten them. It was something that MAI staff had never thought would be an issue, and people fixing their tires soon became a common sight on the farm.

As challenges were averted and resolved, fields began to take shape on the MAI Alyssa farm and tillage was soon completed for the first planting season.

While the initial plowing was taking place, seed began to arrive at the property in Beltu. The seed had been cleaned at government state farms in Ethiopia, and the seed came packed in quintal sacks, which are about 100 kilograms or 220 pounds each. Trying to move the sacks around became quite a chore.

InfoMind hired about 30 men to stack the sacks of seed. They had never stacked grain before, but they were trained in the process. Five or six men ended up doing most of the work, while the other 25 sat around arguing about how to do it. But, in the end, a fairly decent stack was achieved.

Rainstorms during the night were cause of worry, so it was decided to build roofs over the piles of sacks in order to keep them dry.

First Planting

When the fields were plowed and it came time to plant, tractors and wagons were utilized. A recipe of grain and fertilizer was mixed in buckets and dumped into spreaders. Alan Baum determined what the mixture would be, which they then used on a per hectare basis – one quintal dimonium phosphate plus one and a half quintals fertilizer urea plus one and a half quintals wheat.

They did their best to calibrate the spreaders as the seed mixture was dumped into them. It turned out to be quite an efficient way to seed the fields on the Alyssa farm. A spreader would be filled, make a pass down the field, turn around, and spread again. In one day, 120 hectares could be seeded.

This is the method of seeding that is fairly commonly in Ethiopian. The ground is disked over by a disc plow, gone over with a disk harrow to level it out as much as possible, and then broadcast with seed and fertilizer. The ground is then gone over with a disk harrow once more to incorporate the seed into the ground. Disc harrows cultivate the surface of the soil, while plows work the ground deeper.

The ground was hard, so the seed mixture was only able to be incorporated in fairly shallow ground. But, it was done well in spite of the conditions. Alan Baum remarked, “I had my doubts about how [the crop] was going to come up, because usually you just disk it in. There’s no compaction of the soil on top of the seed. And, that’s a necessary thing, usually, to get the moisture to attract to the seeds so the seed has the moisture to germinate and grow.”

Harrows, and roller harrows, didn’t exist in Ethiopia, so MAI had to rely on disks to prepare and seed the farm. It was difficult to describe to the local people what equipment the employees of MAI were looking for.

Field Development

MAI was leased 10,000 hectares of land for the seed farm in Beltu, in a twenty kilometer by five kilometer piece of property. A five kilometer long road cuts through the property north to south. The property then extends 6 kilometers in one direction from the road and 14 kilometers in the other direction.

MAI was not able to clear and plow rectangular fields, due to land issues and conflicts, so the result was misshapen patches of planted ground. Employees used a handheld GPS to map the fields and the total size of land planted during the first season. This GPS data was entered into a computer software program, which then showed the area where grain was being planted.

Crop Progress

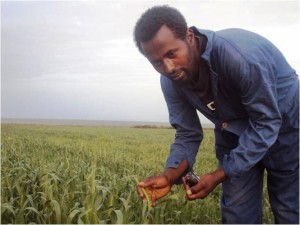

One Week After Planting One week after the seed was planted, small green shoots were already sprouting up from the ground.

Alan Baum said, “First off, I surprised that it was up that high after a week. Where I’m from, our soil is so cold it usually takes two weeks or so to reach this point at least. Another thing is that it did come up… We dug around [and] some of it had come up through about four inches of soil to get to this point.”

There was also a lot of soil that was just shallow and loose, dry dirt. It would only take a rain to sprout the seed left in the ground. Alan could already see that the Alyssa farm would produce a decent crop, and there was still the potential that more seeds would sprout that season. This was also a cause of worry – that there might be too much growth, too many seeds in the ground. In the United States, a farm would normally be planted at a rate of one quintal per hectare. But, in Ethiopia, MAI had planted 50% more to offset the inaccuracies of the planting there.

Two weeks later, in the middle of April, the crop was beginning to take shape. It was progressing a lot better than hoped for, as the tillering of the wheat had already begun.

Tillering

Tillers are multiple stems that are produced from one seed. Tillering is the process that plants go through when they recognize moisture in the soil and determine that it is a good atmosphere to grow. The plants will then shoot out more stems, because they realize that they can sustain more growth. This is usually triggered by cool, wet weather.

In hot, dry climates, like Utah or Idaho, tillering is not very productive. The plants know that in order to survive to sustain another generation of growth, they can only shoot up one or two stems.

On average, the wheat planted in Ethiopia was producing four tillers, or stems, from each seed. In some situations, ten tillers were produced. These were produced without cool weather, but the rains helped. The local people were amazed to see how many stems came from each seed. It was a new idea to them, according to Wes Haws.

Spraying for Weeds

MAI’s weed sprayer was supposed to arrive at the Alyssa property in February, but when it came time to spray for weeds, the sprayer was still three weeks away from arrival. Mekonen Geteneh, an MAI employee, has since then been told that the sprayer was damaged at port and will have to be replaced.

Without the sprayer on site, the challenge arose as to how the fields were going to be sprayed for weeds. Employees at the farm decided to buy 50 backpack sprayers and then hire 50 people to go out and spray the fields. 2,4-D was the only weed control broadly available to MAI in the area, so, a little later than employees would have liked, the growing fields were sprayed with the chemical.

The majority of the weeds at the Alyssa farm were brush that had sprouted up again from the roots, which MAI staff had cleared earlier in the year. The brush growing in the Beltu region of Ethiopia has a large, established root system and it will continually keep trying to grow back. Just spraying 2,4-D by hand would not work very well alone, so many of these bushes and trees had to be pulled out by hand. Spraying the fields with backpack sprayers, rather than a mechanical one, did actually worked quite well, though, and hopefully it will hold back some of the weeds.

A disk ripper would have helped to dig up the root system. Regular tillage would also have helped, but even that would be difficult because the roots and trees there are very hard and difficult to deal with.

2,4-D needs to be sprayed on the wheat late, after the tillers have stopped sprouting. If the chemical is sprayed on too early, it will stop the tillering of the wheat.

Crop Monitoring

Most of the American employees of Morrell Agro Industries had to leave Ethiopia during the months of May and June, due to the national Ethiopian elections taking place. This left the monitoring of the Alyssa grain crop progress to the local people and staff.

Ethiopian farm managers would regularly take pictures of the crop growth, sending them to employees in the United States, so that decisions could be made from a distance. As Alan Baum received various pictures of the growing crops, he had reason to get excited, while being able to see the progress it was making.

One picture, sent to employees in the United States, gave signs that there may be disease problems in the crop. Alan was assured that this was not the case. Most of the pictures that showed crop discoloration were only in the bottom gully washes where there was a lot of water, or near termite mounds. They didn’t believe that there were any rust problems in the crop.

A more recent picture, sent to the States, showed the grain height as it was heading out. It concerned employees that the crop may ripen faster than anticipated, but they were looking forward to a good harvest.

Land Conflicts

Morrell Agro Industries leased 10,000 hectares from the Ethiopian government to develop a seed farm in Beltu. As part of this agreement, the government surveyed the property and identified any people who resided in the area. They were then to compensate the people, by buying the property from them, and the land would be vacated. The property was to be bought with MAI’s lease payment. The lease payment has been made, but the government has yet to pay anyone to move off of the property.

Only two or three percent of the property is actually occupied, but the Ethiopian people do not want MAI to plow the land that they have not been paid for. Their homes are on the land, and it is reasonable that they do not want to move without the proper compensation.

MAI once received a machete through the front of one of their tractors that the local people believed was too close to their property. They do, however, recognize that it is a government problem. But, at the same time, they want to protect what is theirs, and anyone in the same shoes would feel in a similar way.

Land conflicts on the Alyssa farm in Beltu have been constant. Ninety-five percent of the conflicts MAI has been dealing with revolve around the government’s slow compensation for the local people’s farmland. The situation is trying to be resolved, so that work can continue to move along.

When Alan Baum and other MAI employees mapped out the planted fields by GPS, the result was cut up sections here and there. It also showed the areas where ranchers and other local people would simply not let MAI tractors in to clear and plow the land. Some of the local people would create big thorny brush piles as a fence. Loaders could quickly push together the brush and burn it, but that would only increase the conflict with the neighbors.

Paul Morrell said, “What they’re getting, the compensation, I think is fair. I think, they think that it’s fair. They just want to make sure that they get it before they start moving. They’ve got animals they’ve got to deal with… There is a lot of area out there to move; they can find another spot. But, it’s just the process that has to be taken care of.”

The local Ethiopian people don’t have a lot of property, but they have lived there for many years. It is understandable that they don’t want to move. This issue will eventually get worked out, everything just moves at a slower pace in Ethiopia. Communication is always a problem, trying to understand the problem and getting feedback. It’s a constant process to move forward.

Concerns

Army Worms

Alan Baum received pictures from the Alyssa farm, while he was in the United States in May, which showed signs of army worms in the crop. These small green worms can cause trouble, and they will show up in grain crops from time to time, although usually not every year. They will chew on the crop, causing damage, and they have been known to cut the heads off of grain just as they are heading out.

There is a chance that army worms can be devastating to crop yield, although that has not been the case at the Alyssa farm. Spraying has begun on the farm, with backpack insecticide sprayers, to stop the spread of the pests.

Grain Storage

When the first season of grain is harvested at the Alyssa farm in Beltu, it will need to be stored until it gets the Ethiopian government’s stamp of approval to be sold throughout the country. Evan Maxfield is working on the development and construction of grain storage bins on the property. In the meantime, an alternative method of storage had to be found. The solution that MAI employees have come up with is grain silo bags.

Silo bags are anaerobic, or airtight, and their bag structure works quite well to store grain. Each silo bag is only designed for one use. It will be cut through to extract the grain when the time comes to sell the seed.

It is possible that rodents may chew through the bags, but that has yet proved to be a concern. And, with enough people monitoring the bags, they can be kept secure.

It is hoped that by the time MAI harvests their second season of grain, the construction of grain bins on the property will be completed. For the first harvest, however, silo bags and traditional Ethiopian methods of storing grain will have to be implemented. Silo bags may also be used, simultaneously, with grain bins in future harvests, as a storage place for experimental varieties of grain.

Bad Roads

Roads to and from the MAI property in Beltu continue to be an issue. They become mud holes whenever it rains, which creates a difficult stretch of land to traverse to bring in and out equipment and people. Work to improve the roads’ condition is continuing.

Arrival of Equipment

The timely arrival of equipment to the farm in Beltu has also been a concern for the staff working there. As of May 25th, the John Deere dealership that MAI works with in Ethiopia said that all currently shipped equipment had arrived, with the exception of the combine. On May 24th, another shipment of farm equipment made it onto the water and on its way to the country.

The first harvest of the Alyssa farm will be 1,200 hectares, and it will have to be done using just one combine. This is doable, depending on the type of rainfall received, but if it looks as though progress is not being made quick enough, combines can be brought in for hire. Ethiopia is currently going through its dry season, when most farmers are idle, so other combines will be available for the use of MAI.

It is important, however, that at least one combine arrive on the farm so that the staff can learn what it will take to service one there. It is hoped that a combine will hold up better in the Beltu environment than the tractors have, as they will not be tearing into the ground the same way.

The last two tractors in shipment to Ethiopia are on tracks. They require more maintenance and work than tire tractors, but they will not have the multitude of tire problems. They also have more pull and traction, and the problems usually caused by driving them along roads will be nonexistent. MAI also hired Clair Jackson to provide maintenance for equipment on the farm.

An air drill should also be arriving at the Alyssa farm soon, for the use of seeding and fertilizing grain.

Sowing Hope and Prosperity

Morrell Agro Industries’ slogan in Ethiopia is “Sowing Hope and Prosperity.”

In November of 2009, when Paul first visited, the land where the Alyssa farm now is was just brush. Preparing for the farm began in January, clearing small experimental portions to decided how best to clear the ground. Today, roughly 1,200 hectares are cleared, seeded, and under cultivation. When the list of problems that employees of MAI have run into is factored in, it is pretty remarkable what has been accomplished.

Alan Baum said, “We’re trying to do a good thing. There’s a lot of people out there looking at us, hoping that this is a success. Even though we’ve had … a lot of conflicts out there through that area, I get the feel that they want us there. They do. They just want to make sure they’re taken care of before they get cleared off their property.”

Paul Morrell said, “These people out here have never held a job in their life. They’ve never been paid wages in their life. They’ve never worked for wages a day of their life. All of this is brand new to them. They’ve never had taxes withheld from a paycheck before. That was a huge problem when they found out that part of their hourly wage went back to the government.”

At one point, MAI was employing 3,000 local people with work on the Alyssa farm. Other people had seen this work being done, and they came in and established a marketplace right on the farm. They set up their wares under tents or pieces of tarp, feeding people and making a lot of money. Employees of the farm would go there to buy food, radios, soda pop, and other things that they had never had before.

A few months after work began at the Alyssa farm, the Ethiopian government went throughout the country performing their annual food security survey. This survey calculates how much food they need to donate to the community, to make sure that their people don’t starve to death. For the first time in the history of the survey, the people in the Beltu region surrounding the Alyssa farm wil not require government aid. This is due, in part, to the wages that MAI is paying the community to work for them.

Paul Morrell said, “We’re changing an entire culture in this area… 80% of them are positive changes and 20% are going to be negative changes, but overall I think it’s a great thing that these guys are doing out there. And, I’m really, really, really impressed with the progress… made in four months.”

Alan Baum is looking forward to getting the rest of the farm equipment to Beltu so that work can be done there more efficiently. It’s exciting to see what progress is being made.

11 Responses to Morrell Agro Industries – Logan All-Hands Meeting – Project Updates – May 25, 2010